Contemporary politics of the United States foreign policy is unique and famously exciting. Put simply, the United States is a world leader and can not afford to be an isolationist. As a result, its foreign policy affects the entire globe, human society as a whole, and ultimately our individual lives. At this point, one might pause and ask who construct and control the politics of the United States foreign policy process in the first place? The simple paradoxical answers are the president, and or not the president. These conflicted answers do not arrive on the scene by accident. Rather, they are a product of common sense experience, as well as conceptual and practical reasoning. With this paradox in mind, it is crucial to examine and understand the nature of the United States foreign policy process.

The politics of the United States foreign policy process is not inanimate object. There are different views about the way in which U.S. foreign policy is made. One of popular view is that the president of the United States is the preeminent person who makes and controls foreign policy process. We at The Key Group see this is a rather simple and narrow view. In reality, the story of U.S. foreign policy runs much deeper than it appears. At the strongest emphasis, it is paradoxical and extremely complex procedure with considerable ramifications that is highly inseparable from the intricate of the domestic political process. It is embodiment of critical interactions among legislative, executive branches, public and private institutions, various groups and attentive individuals. Thus, beside the president, there are other players in the narrative of the foreign policy process.

The president is one of the major figures who mountain the foreign policy process. Put it differently, what is certain is that the president is on top of all foreign policy process. There is of course, a number of reasons out of this perception. The president of the United States is practically, the commander in chief and the most powerful political actor, certainly. Constitutionally, the president is at the helm of the country. He also occupies very distinctive constitutional roles that give him enormous power to set and implement national and foreign policy agenda. He is the chief of state, voice of the people, commander in chief, chief administrator, chief judicial officer, chief legislator; chief diplomat and many other constitutional roles. These functions give the president enormous power to conduct and operates foreign policy. So, when most people think who makes the U.S. foreign policy, they immediately consider the president.

Virtually, the president is the chief diplomat and chief negotiator. The United States Constitution grants him the power to represent the country in all diplomatic arenas. Further, part of his constitutional duty is to nominate the secretary of state and ambassadors to countries abroad. Also he has the power to receive foreign ambassadors, and to negotiate treaties with other countries. In addition, the president has the right to offer, or withdraw, official U.S. diplomatic relations with foreign governments. Finally, he can enter into executive agreements with foreign governments and, with the advice and consent of the Senate. In that sense, the president has the authority to negotiate treaties that are binding on the United States and have the force of law. Precisely, president can personally lead American diplomatic delegations and negotiate treaties with foreign leaders. For example, in 1972 President Nixon led the American delegation to Moscow to complete the first Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) with the Soviet Union. Similarly, President Carter spent thirteen days negotiating with President Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Menachem Begin of Israel in 1978 to produce the Camp David Accords. President Reagan had four major summits with Soviet leaders Mikhail Gorbachev between 1985 and 1989. President Clinton led the American delegation that attempted to bring a settlement to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Lastly, President Obama has traveled extensively throughout the world, meeting with foreign leaders concerning a variety of national security and economics issues. Finally, US presidents participate every year with leaders from the world’s major economics (G-8) and developing countries (G-20) in summits to discuss measures to contribute to the stability and growth of the international political economy.

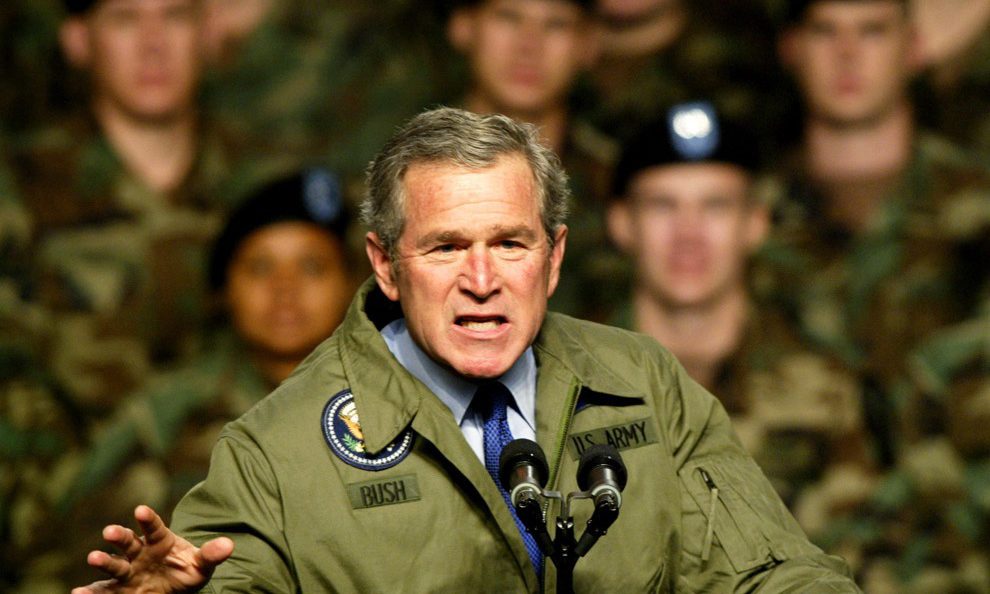

Presidential power and influence on foreign policy is immense. In popular sense, the president is on top of all foreign policy process during the time of war, world disastrous and national security turmoil. As commander in chief, the president has ultimate authority over the military. By virtue of his position as president, he is to be treated as the highest (like a six-star) general, and when he gives an order, members of the military and the Department of Defense comply. This position gives him considerable power to dictate the use of American armed forces including the nuclear power abroad. As an example, in recent history, President George H. W. Bush ordered the uses of military force in Panama 1989, and in the Persian Gulf War in 1991. Another example is when President Clinton led a major NATO bombing campaign in the war in Kosovo. Similarly, President George W. Bush used military forces to lead a “global war on terrorism” in Afghanistan and Iraq. Finally, President Barack Obama ordered the increase of military footprint in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Also, Obama ordered U.S. military forces to participate with NATO in Libya, and most importantly, he uses military forces (Drone) in his war on terror. Hence, as the commander in chief, the president has great leverage and power to use military forces when it is necessary.

The president, undoubtedly, has prime responsibility of foreign policy process. The United States Constitution grants him massive power to set and influence foreign policy agenda and implementations. This appears to be very simple and straightforward. Most importantly, the vast majority of people are taking this view for granted. It seems, this is the dominant and relatively durable perception about the politics of U.S. foreign policy process. But the reality of U.S. foreign policy process is a bit more complicated, and not what appears to be, as exclusively dominated by the president. At the very least, the central aspect of U.S. foreign policy process consists of various actors. Even though, the president is the single center of decision making, there are multiple competing players who have direct and indirect influence in the making of foreign policy process. Consider, for example, Congress, executive branch, different government departments, corporations, businesses, foreign entities, interest groups, mass media, and active individuals. Each of these groups presents different value, agenda and interests. In addition, sometime there are hidden rivalry, and often open and ferocious competitions among these groups.

Ironically, the president has to deal with multiple players. To succeed, the president has to interact with friends and adversaries. Of course, such interactions involve logrolling. In other words, the president has to cooperate, compromise, negotiate, persuade and bring along enough supports to his foreign policy agenda. As a matter of fact, it is quite complicated for the president to deal with multiple interlocutors who hold different agenda and interests. At this point, the implication of such interaction is most likely to be paradoxical. In some respect, sometimes, the president’s interaction with his interlocutors is easy, direct, short and positive. Yet, sometimes the interaction path is barely visible, obscured by the struggle of contending ideas and interests. More often, however, the interaction is difficult, long, sinuous, and marked by detours, roadblocks, and even dead ends.

The politics of U.S. foreign policy embedded in paradox. It is an ordinary sense, people become more united during the eminent of national threats. When it comes to the matter of life and death (think of the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001) people become furious with vengeful rage against their external enemies. As a result, they get more engaged in the politics of foreign policy process and squeeze hard to make their voices loud and clear. Most importantly, Congress, the executive branch, media, businesses, active citizens and general public come together for national cause. In this circumstance, the “overstretch” of political rhetoric about strong patriotism and nationalism.

In a sense, the epic of security, survival, nationalism, compassionate national unity against heinous evil reach its peak and become contagious. To elucidate, war and national unrest are the unified elements for all or at least the majority of the American people. In this respect, adversaries postpone their immediate personal interests, and suspend their differences with their rivals and support the president foreign policy. At such critical time, most of the people only think about security, safety, and severe retributive punishment and humiliated defeat to their foreign enemies. Here, self-interest and collective interest are in perfect harmony. For all and each group, party, individuals and society in general, doing what is best for “Me” and what’s best for “Us” is the same. In other words, such dramatic events of war and imminent national crisis are often the trigger for increased national awareness and unity. At these circumstances, the president represents power, moral influence and the country’s political ideal. Moreover, his foreign policy process receives strong supports from all or most of public and private institutions and general public. Therefore, the president’s power and control of foreign policy process increase immensely. The truth is that this stage of collective minds is exceptionally important time for the president to conduct and execute his foreign policy process.

The president accumulates more power during the time of war and external threats. As we have noted, at time of catastrophes, citizens united and support the president’s foreign policy. At this stage of collective minds, people give the president a blank check to implements his on foreign policy. As a result, the presidential power increases immensely. In other words, the national unification and collective supports grants the president enormous amount power and puts him on top of the foreign policy agenda. The president gains more trust, strong uncontested supports and political will to formulate and implement his foreign policy. In a clear sense, the president becomes a monopoly of the foreign policy process. Very simply, during this time, power is increasingly concentrate in the hand of the president and his executive branch and especially in the White House and the national security bureaucracy. With such consensus support, the president becomes more powerful and luminary figure. He acts with confidence and becomes openly active and often brags about his foreign policy agenda. However, this euphoria of unity and unanimous support is not eternal. It declines and fades away when the eminent national existential threat is over. In other words, it ends shortly when there is no reason for fear, panic, revenge and rage about external threats and enemies. In short, the massive support ends when the insult of national pride is redeemed, and national security and collective self confidence restored.

The politics of U.S. foreign policy, no doubt is murky and paradoxical. The president cannot take the country’s unified position and unanimous support for granted. For different reasons, the massive harmonized supports during war and national emergency time cannot last for ever. It comes to the brink or even to its ends when the situation is back to normal. Moreover, the dilemma is that the collective national position and supports vanished away, and sometime with a bit of disappointments. As a result, the strong unified foreign policy position turns apart and scatter into a web of multiple players and competing rivals. The shocking surprise, the nation’s homogeneity and supports for overall national interests switched into narrow individual interests and often to effervescence controversies. At this point, instead of a single center of decision making process, there are many centers competing for power, influence and interests. Along similar line, the foreign policy process becomes more diffused, and scattered among different competing adversaries. Oddly enough, competition, disagreements and personal interests rise into the surface. Each group strives hard to elevate its own foreign policy agenda and do not surrender them easily. Here, usually, the complexity of the foreign policy process intensifies, and the competitions and tensions among the rivals become increasingly visible. Under this conception, the implication of these complexities, perhaps, diminish the president commands on the foreign policy process. More specifically, these intricacies hinder and even paralyze most of the president foreign policy projects. As a result, the president may merely not be able to act decisively and quickly in most of his foreign policy initiatives.

In a general way, some people might conceive the political phenomenon of U.S. foreign policy process as a curse of the American existence. But, we at The Key Group see that this is the underpinning of democracy and rule of law. We see that underneath of these paradoxes and complexities rest strong rule of law, and a profound spirited logic of democratic values and practices. Certainly, this is the boon of equality and political freedom that prevents tyranny and oppression. Further, the political system that equally allows all citizens to engage in public discourse and reason about their differences and make free choices. One central characteristic of such democratic privilege is about collective decision-making. For that reason, often, the president must interact with different parties, debate, reason, and make compromise about his foreign policy agenda. Interestingly, sometimes the president prevails, and some other times he is challenged by various conflicting actors. This is the way in which the politics of the United States foreign policy is formulated, conducted and managed. Thus, to understand the politics of U.S. foreign policy process is vital to look at the dynamics of national and international political spheres, and especially the unusual circumstance of war and external threats. In short, it is crucial to understand the intricate and ramifications of all actors whom are heavily involved in the making of foreign policy process.

In general, the politics of US foreign policy is an interesting phenomenon. In this regard, for sure, the making of U.S. foreign policy is intricate, dynamic and in rapid changes. No doubt, its evolution, relevance, significance, positive and negative consequence will continue. Certainly, U.S. foreign policy process is no longer static and dominated by the presidents as in World War II, Vietnam War and during the Cold War period. The current American foreign policy process is more pluralistic with complicated sets of values, agenda and interests. As we look to the future, we expect to see the politics of U.S. foreign policy will become more complex. As we reflect on the ground covered so far, the equilibrium of the foreign policy process is dictated by the national and international catastrophes, security emergency, peace and stability. Recognizing the increasing competitive nature of the key national and international stakeholders, the future of U.S. foreign policy process will become thornier. It is clear that each entity will yield agenda and adapts specific strategies and tactics to serve its interests. Such impulses will go all the way and clashes with the president’s foreign policy process. For the foreseeable future, the underlying objective of the politics of US foreign policy is to remain as American as possible, under the circumstances. In practice, once again, that means US foreign policy process, at the end, however, entails paradox, much more complex, but it remains strong and progressive. Ultimately, this calls for more rigorous study and evaluation.

In sum, if the United States domestic politics is a family that shares the same history, democratic values, freedom, reason, paradoxes, complexities and absurdity; then, the politics of U.S. foreign policy is the immediate member of the family. Whatever else can be said about the family, it can be safely asserted that it is a form of paradox. Yet, the common denominator and the endeavors of this family is to work day and night the best strategies that make them survive and prosper. This is what makes the politics of this family so overwhelming significance. The political endeavor of this family, for better or worse, good or ill, affects most of human lives. Look into your own existence and personal life, to your choice of profession, your sudden enrichment or impoverishment; your happiness and misery; isn’t that strange to see some effect on your life is happening precisely because of the politics of the United States foreign policy? Or isn’t? In short, somehow, the politics of U.S. foreign policy will survive the expected and unexpected cruel and awkward circumstances, continue for next while and thrive. Just pause and contemplate for a moment, then navigate and entertain the politics of U.S foreign policy and find out what really is and what is not.